1791 1st ed Addition of Thomas Pennant History of LONDON Britain Westminster London & Westminster ca. 1563 Great Fire PLATES!

Thomas Pennant (1726 – 1798) was a Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian. He was born and lived his whole life at his family estate, Downing Hall near Whitford, Flintshire in Wales.

1791 1st ed Addition of Thomas Pennant History of LONDON Britain Westminster

London & Westminster ca. 1563 & Great Fire PLATES!

Thomas Pennant (1726 – 1798) was a Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian. He was born and lived his whole life at his family estate, Downing Hall near Whitford, Flintshire in Wales.

Main author: Thomas Pennant

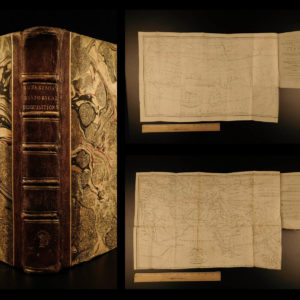

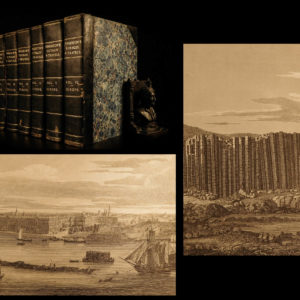

Title: Additions and corrections to the first edition of Mr. Pennant’s account of London.

Published: London : Printed for Robert Faulder, 1791.

Language: English

Notes & content:

- 1st edition addition to original

- Illustrated frontispiece of Charles I

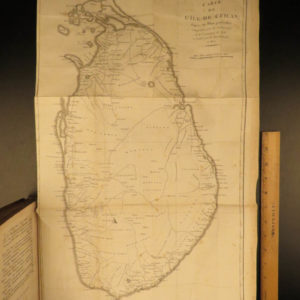

- A large engraved folding plan of London and Westminster ca. 1563

- A large engraved folding plate of London as it appeared at the time of the Great Fire in 1666.

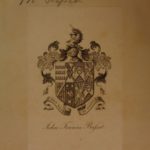

- Provenance: Armorial Bookplate – John Francis Basset

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

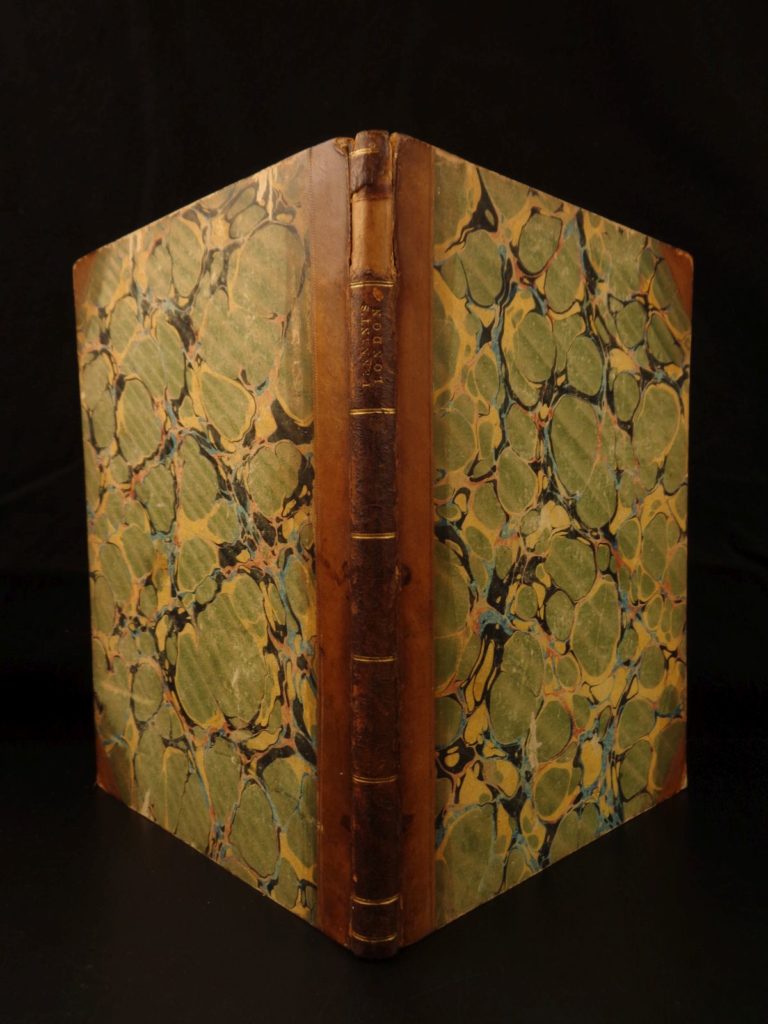

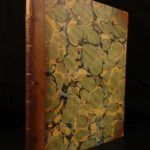

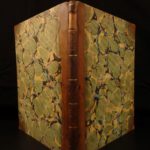

Wear: wear as seen in photos

Binding: tight and secure leather binding

Pages: complete with all 54 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such

Publisher: London : Printed for Robert Faulder, 1791.

Size: ~9.75in X 7.5in (25cm x 19cm)

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Shipping:

Very Fast. Very Safe. Free Shipping Worldwide.

Satisfaction Guarantee:

Customer satisfaction is our priority. Notify us within 7 days of receiving your item and we will offer a full refund guarantee without reservation.

$750

Thomas Pennant (14 June OS 1726 – 16 December 1798) was a Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian. He was born and lived his whole life at his family estate, Downing Hall near Whitford, Flintshire in Wales.

As a naturalist he had a great curiosity, observing the geography, geology, plants, animals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish around him and recording what he saw and heard about. He wrote acclaimed books including British Zoology, the History of Quadrupeds, Arctic Zoology and Indian Zoology although he never travelled further afield than continental Europe. He knew and maintained correspondence with many of the scientific figures of his day. His books influenced the writings of Samuel Johnson. As an antiquarian, he amassed a considerable collection of art and other works, largely selected for their scientific interest. Many of these works are now housed at the National Library of Wales.

As a traveller he visited Scotland and many other parts of Britain and wrote about them. Many of his travels took him to places that were little known to the British public and the travelogues he produced, accompanied by painted and engraved colour plates, were much appreciated. Each tour started at his home and related in detail the route, the scenery, the habits and activities of the people he met, their customs and superstitions and the wildlife he saw or heard about. He travelled on horseback accompanied by his servant, Moses Griffiths, who sketched the things they encountered, later to work these up into illustrations for the books. He was an amiable man with a large circle of friends and was still busily following his interests into his sixties. He enjoyed good health throughout his life and died at Downing at the age of seventy two.

Contents [hide]

1 Family background

2 Interests

3 Scientific work and publications

3.1 Early works

3.2 Tours in Scotland

3.3 Later works

4 Correspondents

5 Works by Pennant

6 Reception

7 Legacy

8 Species named after him

9 Notes

10 References

10.1 Sources

11 External links

Family background[edit]

Bychton, from Pennant’s ‘A tour in Wales’

Downing Hall, Pennant’s lifelong home

The Pennants were a family of Welsh gentry from the parish of Whitford, Flintshire, who had built up a modest estate at Bychton by the seventeenth century. In 1724 Thomas’ father, David Pennant, inherited the neighbouring Downing estate from a cousin, considerably augmenting the family’s fortune. Downing Hall, where Thomas was born in the ‘yellow room’, became the main Pennant residence. This house had been built in 1600 and the front and main entrance were set back between two forward facing wings. By the time the Pennants moved there it was in a state of disrepair and many alterations were set in hand. It had a number of fine rooms including a well-stocked library and a smoking room “most antiquely furnished with ancient carvings, and the horns of all the European beasts of chase”. The grounds were also very overgrown and much effort was put into their improvement and the creation of paths, vistas and pleasure gardens.[1]

Thomas Pennant, miniature by Josiah Wedgewood

Pennant received his early education at Wrexham Grammar School, before moving to Thomas Croft’s school in Fulham in 1740. At the age of twelve, Pennant later recalled, he had been inspired with a passion for natural history through being presented with Francis Willughby’s Ornithology. In 1744 he entered Queen’s College, Oxford, later moving to Oriel College. Like many students from a wealthy background, he left Oxford without taking a degree, although in 1771 his work as a zoologist was recognised with an honorary degree.[2]

Pennant married Elizabeth Falconer, the daughter of Lieutenant James Falconer of the Royal Navy, in 1759 and they had a son, David Pennant, born in 1763. Pennant’s wife died the following year and fourteen years later he married Ann Mostyn, daughter of Sir Thomas Mostyn of Mostyn, Flintshire.[3]

Interests[edit]

A visit to Cornwall in 1746–1747, where he met the antiquary and naturalist William Borlase,[4] awakened an interest in minerals and fossils which formed his main scientific study during the 1750s. In 1750, his account of an earthquake at Downing was inserted in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, where there also appeared in 1756 a paper on several coralloid bodies he had collected at Coalbrookdale, Shropshire. More practically, Pennant used his geological knowledge to open a lead mine, which helped to finance improvements at Downing after he had inherited the estate in 1763.[5]

In 1754, he was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries but by 1760 he was happily married and resigned his fellowship because “my circumstances at that time were very narrow, my worthy father being alive, and I vainly thought my happiness would have been permanent, and that I never should have been called again from my retirement to amuse myself in town, or to be of use to the society.”[6] When his financial circumstances later improved, he became a patron and collector. He amassed a considerable collection of works of art, many of which had been commissioned and which were selected for their scientific interest rather than their connoisseur value. He had several works by Nicholas Pocock representing topographical landforms, mostly in Wales, and others by the artist Peter Paillou, probably commissioned, representing different climate types. His portrait by Thomas Gainsborough shows him as a country gentleman. Also included in the “Pennant Collection”, housed at the National Library of Wales, are many watercolours by Moses Griffiths and John Ingleby, and some drawings by Pennant himself.[2]

The artist Moses Griffiths, a native of Bryncroes in the Llŷn Peninsula, provided illustrations to most of Pennant’s books.[2] He was employed full-time by Pennant and accommodated at Downing. Many of these paintings are included in the Pennant Collection held by the National Museum of Wales.[2] Another artist whom Pennant employed on an occasional basis was John Ingleby of Halkin. He mostly supplied town scenes and vignettes.[2]

Scientific work and publications[edit]

Early works[edit]

“The Heron” engraved by Peter Mazell from painting by Peter Paillou, in Pennant’s British Zoology

Pennant’s first publications were scientific papers on the earthquake he had experienced, other geological subjects and palaeontology. One of these so impressed Carl Linnaeus, that in 1757, he put Pennant’s name forward and he was duly elected a member of the Royal Swedish Society of Sciences. Pennant felt very honoured by this and continued to correspond with Linnaeus throughout his life.[4]

Observing that naturalists in other European countries were producing volumes describing the animals found in their territories, Pennant started, in 1761, a similar work about Britain, to be called British Zoology. This was a comprehensive book with 132 folio plates in colour. It was published in 1766 and 1767 in four volumes as quarto editions, and further small editions followed. The illustrations were so expensive to produce that he made little money from the publication, and when there was a profit, he gave it to charity. For example, the bookseller Benjamin White, brother of the naturalist Gilbert White,[7] received permission, on payment of £100, to publish an octavo edition, and the money thus raised was donated to the Welsh Charity School. Further appendix volumes were added later and the text, largely written from personal observations, was translated into Latin and German.[8]

The book took several years to write and during that time, Pennant was struck by personal tragedy when his wife died. Soon afterwards, in February 1765 and apparently as a reaction, he set out on a journey to the continent of Europe, starting in France where he met other naturalists and scientists including the Comte de Buffon,[4] Voltaire, who he described as a “wicked wit”, Haller and Pallas, and they continued to correspond to their mutual advantage. He later complained that the Comte used several of his communications on animals in his Histoire Naturelle without properly attributing them to Pennant.[9] His meeting with Pallas was significant, because it led Pennant to write his Synopsis of Quadrupeds. He and Pallas found each other’s company particularly congenial, and both were great admirers of the English naturalist John Ray. The intention was that Pallas would write the book but, having written an outline of what he planned, he got called away by the Empress Catherine the Great to her court at St Petersburg. At her request he led a “philosophical expedition” into her distant territories that lasted six years, so Pennant took over the project.[10]

In 1767 Pennant was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. About this time he met the much-travelled Sir Joseph Banks and visited him at his home in Lincolnshire. Banks presented him with the skin of a new species of penguin recently brought back from the Falkland Islands. Pennant wrote an account of this bird, the king penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus), and all the other known species of penguin which was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.[11]

Tours in Scotland[edit]

Elephant and bison, from the History of Quadrupeds (1793)

While work on the Synopsis of Quadrupeds was still in progress, Pennant decided on a journey to Scotland, a relatively unexplored country and not previously visited by a naturalist. He set out in June 1769 and kept a journal and made sketches as he travelled. He visited the Farne Islands off the Northumberland coast on the way and was much impressed by the breeding seabird colonies. He entered Scotland via Berwick-on-Tweed and proceeded via Edinburgh and up the east coast, continuing through Perth, Aberdeen and Inverness. His return journey south took him through Fort William, Glen Awe, Inverary and Glasgow. He was unimpressed by the climate but was interested in all he saw and made enquiries about the local economy. He described in detail the scenery around Loch Ness. He enthused over the Arctic char, a fish new to him but did not mention a monster in the lake. He observed red deer, black grouse, white hares and ptarmigan. He saw the capercaillie in the forests of Glenmoriston and Strathglass and mentioned the pine grosbeak, the only occasion on which it has been recorded from Scotland. He enquired into the fisheries and commerce of the different places he passed through and visited the great houses, reporting on the antiquities he found there. He finished his journey by visiting Edinburgh again and travelling through Moffat, Gretna and Carlisle on his way back to Wales, having taken about three months on his travels.[12] On his return home, Pennant wrote an account of his tour in Scotland which met with some acclaim and which may have been responsible for an increase in the number of English people visiting the country.[13]

In 1771 his Synopsis of Quadrupeds was published; a second edition was expanded into a History of Quadrupeds. At the end of that same year, 1771, he published A Tour in Scotland in 1769. This proved so popular that he decided to undertake another journey and in the summer of 1772, set out from Chester with two companions, the Rev. John Lightfoot, a naturalist, and Rev. J. Stewart, a Scotsman knowledgeable in the customs of the country. They travelled through the Lake District, Carlisle, Eskdale, which Pennant much admired, Dumfries and Glasgow. In passing, he was fascinated by the account of the inundation of the surrounding farmland by a bursting out of the Solway Moss peatbog. The party set sail in a ninety-ton cutter from Greenock to explore the outer isles. They first visited Bute and Arran and then continued to Ailsa Craig. Pennant was interested in the birds, frogs and molluscs and considered their distribution. The boat then rounded the Mull of Kintyre and continued to Gigha. They would have continued to Islay but were becalmed. During this enforced idleness, the ever-industrious Pennant started on his ancient history of the Hebrides. When the wind picked up they continued to Jura.[14]

Cottage on Islay, by John Cleveley the Younger, in Pennant’s A Tour in Scotland, and Voyage to the Hebrides 1772

Here, as elsewhere, they were hospitably welcomed, lent horses to explore the island and shown the principal sights and the improvements that had been made. Pennant records the scenery, customs and superstitions of the inhabitants with many an anecdote. They later reached Islay where Pennant found geese nesting on the moors, a more southerly nesting site for geese than had previously been recorded. Their journey next took them to Colonsay, Iona and Canna and eventually to Mull and Skye. A projected journey to Staffa was prevented by adverse weather. Returning to the mainland, the party paid off their boat and attempted to travel northwards to the most northerly tip of Scotland. In this they were thwarted and had to retrace their route, having met bogs, hazardous rocks and country that even their “shoeless little steeds” had difficulty in negotiating.[14] They returned to Skye for a while before parting company, Pennant continuing his tour while his companions returned to England, Lightfoot carrying with him most of the material he would later use when writing his Flora Scotica. Pennant visited Inverary, Dunkeld, Perth and Montrose. In the latter, he was surprised to learn that sixty or seventy thousand lobsters were caught and sent to London each year. He then travelled via Edinburgh, through Roxboroughshire and beside the River Tweed to cross the border at Birgham. Once in England he travelled rapidly home to Downing.

Categories

European History

Voyages & Exploration & Maps

Authors

Thomas Pennant

Printing Date

18th Century

Language

English

Binding

Leather

Book Condition

Good

Collation

Complete